Matilda Elizabeth Pauley

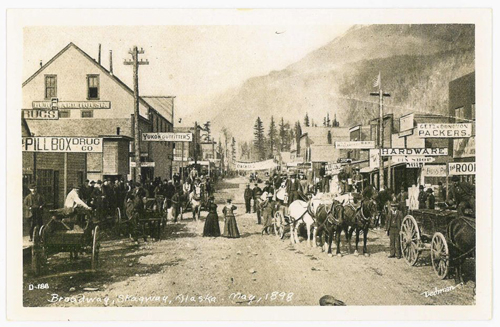

Not everyone who was drawn to the Yukon in 1897 had dreams of striking it rich on a placer claim. There were also plenty of opportunists who went north to “mine the miners” by supplying the miners' need for supplies for the challenging trip north. From pick axes to prostitutes—everything could be had for a price on Alaska’s gold rush frontier. The town of Skagway, nestled at the base of the White Pass Trail, was among the wildest of these outposts; its population exploded almost overnight when gold was discovered along a Klondike River tributary just a year earlier in 1896.

One of Skagway’s more respected entrepreneurs was a gentleman named Claude Arlington Pauley. He managed the Pacific Meat Market on Fifth Avenue during that wild gold rush summer of 1898. He had married a girl from Auburn named Matilda Elizabeth in 1892; they married in Pendleton, Oregon. Sometime after the marriage, the couple returned to Auburn where Claude mastered the butcher’s trade and where, in June of 1897, Matilda gave birth to a little girl whom they named Verda. It was probably the following spring when Mr. Pauley took his wife and daughter with him to Skagway, caught up in the excitement of the Alaska gold rush.

Skagway, Alaska. May 1898.

Their business might have thrived, but their personal life soon unraveled. First, baby Verda took sick. She died on May 19. Remarkably, “teething” was listed as her cause of death.1 According to the Skagway News of June 14, Mrs. Pauley contracted a bad cold while at the cemetery for her baby’s funeral. It would appear that the cold progressed into pneumonia. The newspaper reported, “The attending physician succeeded in subduing the lung difficulty, but peritonitis set in, and in spite of the best care and attention, the lady gradually grew weaker until Saturday afternoon, when she quietly passed away in the presence of her sorrowing husband and immediate friends.”2

Although Matilda was buried with her baby in Skagway’s Gold Rush Cemetery, nearly half the people who died in Skagway during the years from 1897-1908 were eventually returned to their homes and families in other places.3 The same June 14 obituary reported, “The body of mother and child were interred in the Skagway cemetery, for the present, but this fall they will be taken up and removed to the cemetery at Auburn, Wash., their former home.”

Despite the devastating loss of his family, Claude Pauley was not yet willing to give up on his dream of striking it rich in Alaska. Thinking there might be financial reward in operating pack trains over the White Pass summit, he shipped 32 horses from Seattle to Skagway, but after the first trip over the trail, only 12 survived. In fact, by the fall of 1898, the valley below the White Pass trail was littered with the bodies of hundreds of dead horses. Author Jack London described the scene that inspired the nickname “Dead Horse Trail” for the White Pass: “Men shot them [horses], worked them to death and when they were gone, went back to the beach and bought more. Some did not bother to shoot them, stripping the saddles off and the shoes and leaving them where they fell. Their hearts turned to stone—those which did not break—and they became beasts, the men on the Dead Horse Trail.”4

While Claude was engaged in this grisly business in Alaska, the bodies of Matilda and baby Verda were indeed sent home to Auburn for reburial. Claude’s brother Luther still resided in Auburn with his own family, and he probably made all of the necessary arrangements on his brother’s behalf. Claude himself remained in Alaska for several more years as he attempted to capitalize on the country’s final gold rush. A later biographical sketch, published around 1940, summarized his activities there:

"In addition to his extensive trade, Mr. Pauley freighted, mined and teamed during his Alaskan residence, and met many interesting characters of that period. On one trip of ten days from Lake Bennett to Dawson, he endured bitter cold of 50 degrees below zero and fought against time to make Dawson before the river froze, arriving only six hours before the winter freeze-up, but landed the grain he had hauled from Lake Bennett and made a handsome profit."5

After several years, Claude married another Auburn girl, Ella Pennington Gove, widow of Hiram Gove, in Vancouver, British Columbia. Together they raised her son John Gove, settling eventually in southern Oregon. Claude resumed the butcher trade, his adventurous Yukon years being well behind him. He died in Klamath Falls in 1959 and is buried with Ella in the Rest Haven Cemetery in Jackson County, Oregon.

As for Matilda and baby Verda’s final resting place, it’s impossible to say for certain where they ended up. Auburn’s Mountain View Cemetery was open by the time of their deaths, but its surviving records go back only as far as 1907. If they are there, they are in an unmarked grave and do not appear in the cemetery’s records. It seems more likely, however, that they are at the Auburn Pioneer Cemetery. Again, there is no tombstone bearing their names, but there is a small notation on both of the earliest cemetery maps that could indicate their plot. “Mrs. Paley,” is all the notation says—no first name and no dates are included. The entry is just one letter off from our Mrs. Pauley’s name, and, while I cannot locate any trace of a “Paley” family in the Auburn area during this era, we certainly have documentation that Matilda and Verda Pauley were buried here in Auburn, forgotten casualties of the Alaska Gold Rush.

1National Park Serivce Klondike Gold Rush Historic Park website, list of those buried in the Gold Rush Cemetery, including causes of death, Aug. 2011. http://www.nps.gov/klgo/historyculture/

2Mrs. Pauley’s obituary was published in the Skagway News on June 14, 1898, and was reprinted in the Gold Rush Cemetery guidebook—see listing below.

3Choate,Glenda J. Skagway, Alaska’s Gold Rush Cemetery. Skagway: Lynn Canal Publishing, 1989. (pp. 24-25.)

4This passage is found in London’s book The God of His Fathers in a chapter titled, “Which Make Men Remember.”

5Sisemore, Linsy, ed. and Rachel Applegate Good, Historian. History of Klamath County, Oregon: its Resources and its People, Illustrated. Publisher unknown: 1942.