Learning a second language is a bit like returning to childhood. One finds oneself chanting an unfamiliar alphabet until it becomes second nature while, at the same time, immersing oneself in the endless process of acquiring new vocabulary words, just as a toddler does. Eventually one learns to read from books that are mostly pictures, returning to childhood realms of scaly dragons or perhaps small animals dressed in fetching Victorian frocks. From there, chapter books eventually wean the leaner off of imaginative illustrations and onto weightier texts and subjects.

This was the position I was in several years ago as I learned the Esperanto language. I had passed the picture book phase and was ready to take on chapter books that could more fully develop a story. The books I found included titles such as La Sorcisto de Oz, La Adventuroj de Alicia en Mirlando, and even Winnie-la-Pu. The same familiarity that might have helped you identify these titles as The Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, and Winnie-the-Pooh helped me find my way through the narratives. Comprehension goes up immeasurably when one knows the general direction of the story. In fact, I wasn’t sure I was ready for a novel-length book—even a children’s book—that didn’t offer me that comforting air of familiarity. But that’s precisely when I discovered Bela Joe, an antique Esperanto book offered for sale in an online auction. I took a chance on this unfamiliar book and placed a low-ball bid. As you might imagine, there is very little competition for children’s literature in Esperanto, and the book soon arrived at my door.

This was the position I was in several years ago as I learned the Esperanto language. I had passed the picture book phase and was ready to take on chapter books that could more fully develop a story. The books I found included titles such as La Sorcisto de Oz, La Adventuroj de Alicia en Mirlando, and even Winnie-la-Pu. The same familiarity that might have helped you identify these titles as The Wizard of Oz, Alice in Wonderland, and Winnie-the-Pooh helped me find my way through the narratives. Comprehension goes up immeasurably when one knows the general direction of the story. In fact, I wasn’t sure I was ready for a novel-length book—even a children’s book—that didn’t offer me that comforting air of familiarity. But that’s precisely when I discovered Bela Joe, an antique Esperanto book offered for sale in an online auction. I took a chance on this unfamiliar book and placed a low-ball bid. As you might imagine, there is very little competition for children’s literature in Esperanto, and the book soon arrived at my door.

Although I had never heard of Bela Joe (or Beautiful Joe, its title in English), I discovered that it was a best-seller in its day. Originally published in 1893 by Canadian author Marshall Saunders, Beautiful Joe was, in fact, the first book to ever sell more than a million copies in Canada. It was the story of an unloved puppy born in the run-down stable of the horse who pulled the morning milk wagon through their small hometown. The cruel milkman who owns the stable abuses his animals, eventually killing all of Joe’s littermates (described in horrific detail) before turning his evil attentions on poor Joe. In a drunken rage, the milkman pins Joe, calls for a hatchet, and hacks off the helpless puppy’s ears and tail. The disfigured, desperate puppy is then rescued by the children of a neighboring family. Because his appearance is so appalling, they give him the ironic name “Beautiful Joe.” The remainder of the novel recounts Joe’s gratitude for his new family and his adventures with the adoring children—told in his own words.

Interesting subject matter for a kids’ book, don’t you think? I’m not sure any modern day publisher could be convinced to market such a dark story as children’s literature. But in the late 1800’s, publishing a book like Beautiful Joe wasn’t just a good idea, it was actually just one example of a growing genre of similar, first-person narratives told from the perspective of abused animals—a genre that had been spawned, single-handedly, by the resounding success of a similar novel published in 1877: Anne Sewell’s Black Beauty.

Although you probably haven’t heard of Beautiful Joe, there is little doubt that you have at least a passing familiarity with Black Beauty. It’s the imaginative story of a horse, told in his own words, who was born on a bucolic farm in England. The story begins with his memories of his mother and companions living an idyllic life on an estate where they are well cared for and happy. Unfortunately, Beauty’s fate soon takes him away from rural comforts; he is brought into the midst of urban squalor in London, forced to earn his keep pulling a carriage under the most depressing and difficult circumstances.

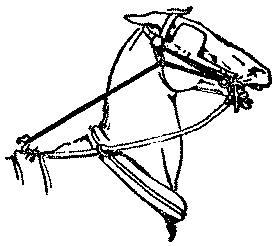

Sewell describes in great detail some of the common practices in the carriage horse industry of her day, always from the perspective of the helpless animal forced to endure them. She describes how the fashion of the times called for docked tails on horses, and the pain this procedure caused as it was inflicted without any medications. She also took issue with the practice of using blinkers (those piratical eye patches frequently attached to bridles) to partially block the horse’s vision; through Sewell, Beauty complains about how awful it is to perform his job under this needlessly inflicted sensory handicap. But perhaps most harrowing is Sewell’s description of the bearing rein, a piece of harness that runs from the bit in the horse’s mouth through the top of the bridle and then down to his withers, creating a sort of pulley system. The leverage created by the rein forces the horse to hold his head up and keep his neck fully arched, an unnatural position that prevented horses from leaning forward into the work of pulling. The resultant air of military attention appealed to the fashion-conscious Victorians, but the impact on horses, over time, was crippling. And all of this was so much easier for readers to grasp when told from the victim’s own viewpoint. In fact, the outrage spawned by Black Beauty resulted in a movement to ban the bearing rein altogether.

Sewell describes in great detail some of the common practices in the carriage horse industry of her day, always from the perspective of the helpless animal forced to endure them. She describes how the fashion of the times called for docked tails on horses, and the pain this procedure caused as it was inflicted without any medications. She also took issue with the practice of using blinkers (those piratical eye patches frequently attached to bridles) to partially block the horse’s vision; through Sewell, Beauty complains about how awful it is to perform his job under this needlessly inflicted sensory handicap. But perhaps most harrowing is Sewell’s description of the bearing rein, a piece of harness that runs from the bit in the horse’s mouth through the top of the bridle and then down to his withers, creating a sort of pulley system. The leverage created by the rein forces the horse to hold his head up and keep his neck fully arched, an unnatural position that prevented horses from leaning forward into the work of pulling. The resultant air of military attention appealed to the fashion-conscious Victorians, but the impact on horses, over time, was crippling. And all of this was so much easier for readers to grasp when told from the victim’s own viewpoint. In fact, the outrage spawned by Black Beauty resulted in a movement to ban the bearing rein altogether.

Unfortunately, as with most experiences from early childhood, we tend to forget such details and retain just the feelings they inspired. When we think of carriage horses, we tend to think of them as pitiful, tortured creatures, suffering at the hands of uncaring humans. We don’t pause to analyze if the circumstances that lead to these conclusions are still valid, if they ever were. And since few of us have any direct experience of the lives of carriage horses, this legacy of pity and outrage that has been handed down to us by Black Beauty remains the single, unchallenged—perhaps even unconscious— source of our beliefs about the lives of these animals. It has become immutable part of the hive-mind for those of us living outside of the world of working animals.

Because of the current controversy in New York surrounding the fate of the Central Park carriage horses, I’ve given some thought to the seeds of outrage that Anna Sewell unknowingly planted with her best-selling novel. I’ve been analyzing Jon Katz’s photos of these horses to help guide this analysis. Since I live on the opposite side of the country, this is as close as I can reasonably get.

In Katz’s photos, I see no evidence that carriage horses are forced to endure tail docking. But is this because the practice was recognized as cruelty or because it simply passed out of fashion? Do we physically alter other animals to satisfy the whims of fashion? Certainly there are dog breeds that traditionally endure ear docking even today. Unlike in Victorian England, these procedures are presumably carried out by veterinarians and under anesthesia. Some animal lovers would argue passionately that the practice is nevertheless cruel, but, since there is still enough demand for the practice that it endures, it would be difficult to reach that categorical conclusion. Regardless, since we no longer dock carriage horses’ tails, it’s a moot point.

Sewell described Black Beauty suffering from the restricted vision resulting from the use of blinkers. I see blinkers present in every photo that Jon Katz has published of carriage horses in harness. If the practice of restricting a working horse’s side vision is cruel, why does it persist today?

The answer, of course, goes to the anthropomorphism of animals. When we imagine ourselves laboring in the streets with artificially restricted vision, of course we’re alarmed. How could any person be expected to carry out his work efficiently—or even safely—under those circumstances? But have we ever considered the impact of sensory stimulation on horses? Anna Sewell, unfortunately, lived far too early to review the studies that eventually explored this issue. Certainly Dr. Temple Grandin, in far more recent times, has helped the public to understand that reducing sensory input endured by animals in stressful situations, is, in fact, one of the more humane things we can do for them. She has revolutionized the livestock industry by designing processes and equipment that intentionally limit stimulation. Blinkers on horse bridles operate on the same, ultimately beneficial, principle. Some may think them cruel, but we could just as easily argue that forcing horses to work in an urban environment without their benefits would be the real cruelty.

The answer, of course, goes to the anthropomorphism of animals. When we imagine ourselves laboring in the streets with artificially restricted vision, of course we’re alarmed. How could any person be expected to carry out his work efficiently—or even safely—under those circumstances? But have we ever considered the impact of sensory stimulation on horses? Anna Sewell, unfortunately, lived far too early to review the studies that eventually explored this issue. Certainly Dr. Temple Grandin, in far more recent times, has helped the public to understand that reducing sensory input endured by animals in stressful situations, is, in fact, one of the more humane things we can do for them. She has revolutionized the livestock industry by designing processes and equipment that intentionally limit stimulation. Blinkers on horse bridles operate on the same, ultimately beneficial, principle. Some may think them cruel, but we could just as easily argue that forcing horses to work in an urban environment without their benefits would be the real cruelty.

Bearing reins, despite the ardent intensions of Sewell’s fans, also persist into the present day. I’m no expert on horse tack and livery, but such reins appear to be evident in several of Katz’s photos. That said, they do not appear to be employed to force the horses into maintaining an unnatural posture. Unlike the illustrations from Sewell’s day, the reins in Katz’s photos appear to have a great deal of slack between the top of the bridle and the horse’s withers. Without interviewing carriage drivers, I couldn’t tell you what their true purpose is, but I suspect it’s the same as the reins used on any riding horse—to establish communication between the animal and the human, a means for the human to communicate direction to the horse or to tell him when to slow or stop. It does not appear that the rein is being used to force the horse to “stand at attention.” I see no evidence of cruelty by its presence in these photos.

Black Beauty obviously had a profound impact on the carriage horse industry, but, even more importantly it touched a nerve with the general public. It virtually propelled the nascent Humane Society movement from sleepy beginnings in England across the Ocean to North American and even beyond to Australia. Beautiful Joe, in fact, was written as a contest entry for one of these early societies in New England; the society had sponsored a writing contest in order to generate sympathy for the sorts of animal cruelty highlighted in Black Beauty (which is why Beautiful Joe was set in Maine rather than the author’s native Canada). Even in the few years between the publication of the two books, the carriage horse had become such an entrenched symbol of animal cruelty that Saunder’s created the tone for Joe’s “autobiography” by first describing the horrendous conditions and treatment endured by the friendly milk horse in scenes already potently familiar from Black Beauty. Saunders actually referenced the presence of Sewell’s book in the home of Joe’s saviors. Even by that time, less than 20 years after Black Beauty was published, the carriage horse had become the virtual poster child of the entire humane movement.

This legacy was built on unshakable narratives, delivered by appealing and pathetic first-person protagonists and served to most of us at a time in childhood that predated objectivity or analysis. In some cases, the narrative had been designed to support specific political goals. For better or worse, carriage horses remain firmly harnessed to Black Beauty’s legacy even today. If these modern horses require liberation, perhaps we can make an attempt to liberate them from our own childish beliefs built on the agendas of a previous century. Only then can we begin to look at their circumstances with any semblance of objectivity.