Last week I attended the opening of Finally Found Books. They moved to a location literally just around the corner from my house! While there, I discovered an antique book with an inscription that I could work with. Like a tombstone, it included a full name and date, and implied a Washington location. Every book includes a story between its covers, but a used book often has a story that can’t be found within its pages—the story of its previous owner.

If Wenatchee, Washington is synonymous with one thing, it’s apples. In early September, when Bonnie Jean Hermann celebrated her fifth birthday, it would have been harvest time. The air would have been redolent with the crisp scent of cider and spiced applesauce. Even in 1930, as the Great Depression tightened its death grip on the American economy, Wenatchee autumns would have been alive with the activity of the local orchardists and itinerant workers who flocked in each year to harvest the crop.

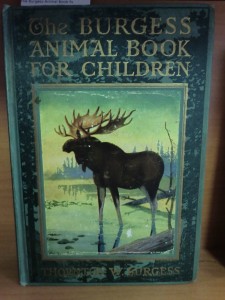

Bonnie’s father Harry Hermann, the owner of a local drug store, was able to support his family while remaining in Wenatchee year round throughout the Depression. Her mother Lorena no doubt tracked the family’s expenses carefully, making it her mission to stretch every dollar as far as possible during those challenging days. Still, Lorena was able to purchase a special book and lovingly inscribe it for her youngest daughter on her special day: “Happy Birthday to Bonnie Jean Hermann from Mother, Sept. 4, 1930.”

With no pictures except for its beautiful cover, The Burgess Animal Book for Children would have been an ambitious gift for such a little girl, but Bonnie had two older sisters. Kay was only 7 years old in 1930, but at age 12, oldest sister June could have easily spent time reading out loud to the littler girls.

As the years passed, the Hermann girls, one by one, graduated high school in Wenatchee. However, sometime after 1942 Harry relocated the family to Seattle where he passed away in 1948. Although her two sisters eventually married and established homes of their own, Bonnie Jean remained with her beloved mother for the rest of the older woman’s life. Lorena died in Arizona in 1977; we presume Bonnie Jean was at her side.

What became of Bonnie after that? There was evidence that while she was living in Phoenix in 2001, she acquired her sisters’ interest in the family home back in Wenatchee. After that, she disappears from the available records. She could still be alive, living her life anonymously, maybe in Arizona, maybe in Washington State. I can’t find her.

But I found her book tonight.

Happy Birthday, Bonnie Jean Hermann—wherever you are.