Listen E. Baldwin, despite having a given name that was both unique and good advice, was instead known by his middle name from his earliest days: Earl. He was a typical New York farm boy, born in the village of Jackson in 1878, the first child in a large family that relocated to nearby White Creek while the boys were still small. As they grew up, Earl and his three much younger brothers—Arty, Charlie, and George—became their father Hiram’s crew, working tirelessly to care for the animals and the crops as soon as they were old enough to hold a hoe. Their mother Lucinda gave birth to her first little girls only after fulfilling her husband’s requirement for enough sons to run the farm—or so it seemed to the boys. A new world of petticoats and pin curls, hair ribbons and high button shoes arrived with the two tiny girls, mystifying but amusing the contingent of older brothers who made it their business to protect their little sisters from the difficult realities of farming in upstate New York.

Earl assumed his own life would follow the same blueprint as his parents’ when he married a local girl with a unique name of her own. Danna was only 18 when they wed; Earl was 25. He had waited, wisely, until his father was ready to carve acreage off of the family farm so that he could start his own farm and his own family at the same time—a new life coincidentally set to begin in the earliest days of a brand new century. He was thrilled when on one fine May morning Danna confided in him that their first child was one its way. Earl whooped in the dooryard, spinning Danna in a circle that scattered the chickens and sent their collie dog barking in delighted confusion. By Earl’s calculations, his son would be old enough to start learning to help with the farm work just as his younger brothers would leave their dad’s place to start families of their own. It was so easy for Earl to visualize what was to come; he had only to remember his own childhood to see the past repeating itself happily into the future.

That fall (1904), Earl had an earnest conversation with his three teenaged brothers about their usual Halloween hijinks. He pleaded with them to show some compassion to Danna if not to him. She was due to give birth at any time and could not possibly be expected to cope with pranks like overturned outhouses or soaped up windows. As Earl spoke, Charlie dragged the toe of his boot through the scattered straw on the barn floor in a guilty way. Arty promised they would behave while staring fixedly at the ground. And George gave Earl his personal assurance that he’d beat anyone who violated Danna’s peace into a bloody pulp. The new baby, who still existed only in theory as far has his brothers were concerned, was already changing Earl in unanticipated ways.

Two days after that uneventful Halloween, Danna finally gave birth to a little girl just as the sun peeked over the horizon on a grey Wednesday morning. Of course Earl knew that such an arcane eventuality as a girl child was possible, but it really hadn’t occurred to him to plan beyond his own experience of sons arriving first. But he wasn’t concerned. There’d be more babies, and still plenty of time for the sons he knew he would eventually need to keep the farm going. Danna suggested that they name the delicate, grey-eyed infant Theresa, and Earl readily agreed as he stared into the baby’s drowsy, pink face for the very first time. No, Theresa wasn’t a son, but she was beautiful, and she was his, and he was smitten.

But the future continued to unfold in an unrelenting departure from Earl’s plans. His wife Danna, despite all odds, did not become pregnant again. And little Theresa turned out to be a delicate child, frequently ill and capturing Danna’s time and attention more fully than Earl had even dreamed possible. As his brothers drifted away to lives of their own, oldest son Earl was left to shoulder the burden of not only his own farm, but his aging father’s as well. It wasn’t in Earl’s nature to ask for help, but he found himself frequently still at his chores as the moon rose, repairing fences or hauling water to the milk cows with only his collie dog for silent company. When he thought of the future, he could only see his work mounting without cease. A niggling worm of desperation had taken hold of his heart. He couldn’t help but make a repeated wish that something would break the log jam of work and worry; something eventually had to give.

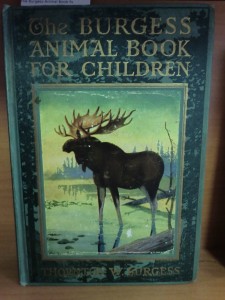

And change did come, but not in a form Earl would ever have wished for or anticipated. It happened just after Halloween when Theresa was six years old. She was sick again, probably exposed to some bug or another by one of her schoolmates. There always seemed to be some sickness passed from child to sniffling child at the school, and Theresa could never dodge any of it. Danna even kept her at home in her bed over Halloween, although she was too sick to protest the decision. Her parents hoped she would recover in time for the small birthday party they’d planned for her on November 2, but despite the doctor’s best efforts, Theresa did not rally. Instead, she declined steadily, her breathing worsening until it became an alarming wheeze that kept even the dog agitated while anchored firmly to her beside. Finally, on November 2—her seventh birthday—Theresa passed away at home, her desperate parents pacing at her bedside. Earl didn’t think Danna would ever stop crying. And he didn’t think he’d ever be able to look at himself in the mirror, knowing the secret wish he’d made but never even voiced out loud. He scraped together enough money for a marble tombstone for Theresa’s grave topped with a small lamb, still feeling like her death was probably in some way his fault.

Theresa died in 1911, well before the discovery of antibiotics or the arrival of childhood vaccinations. In those days, the death of a child was a tragically common occurrence, and parents were expected to soldier on. That’s what Earl and Danna did, attending Christmas services and 4th-of-July picnics, and tending their house and farm. They even continued to try to have more children through increasingly joyless couplings that never again resulted in conception. By 1920 Earl had largely given up on his childhood dreams of a family farm. He took a job as a laborer with the railroad, leaving Danna at home to care for the chickens and the lethargic hound that replaced their collie dog not long after Theresa’s death. The Great War had finally ended, but prohibition had arrived with a joyless finality. The days of frivolous, lighthearted happiness seemed to have passed by before they had even fully arrived for the Baldwins. Certainly this was true for Danna; she was a mother without a child, and (in those days) a woman without a role. She died in 1926 at age 41, an age at which she had probably lost all hope of ever being a mother again.

Theresa died in 1911, well before the discovery of antibiotics or the arrival of childhood vaccinations. In those days, the death of a child was a tragically common occurrence, and parents were expected to soldier on. That’s what Earl and Danna did, attending Christmas services and 4th-of-July picnics, and tending their house and farm. They even continued to try to have more children through increasingly joyless couplings that never again resulted in conception. By 1920 Earl had largely given up on his childhood dreams of a family farm. He took a job as a laborer with the railroad, leaving Danna at home to care for the chickens and the lethargic hound that replaced their collie dog not long after Theresa’s death. The Great War had finally ended, but prohibition had arrived with a joyless finality. The days of frivolous, lighthearted happiness seemed to have passed by before they had even fully arrived for the Baldwins. Certainly this was true for Danna; she was a mother without a child, and (in those days) a woman without a role. She died in 1926 at age 41, an age at which she had probably lost all hope of ever being a mother again.

And Earl? He didn’t stay with the railroad for long. By 1930 his was back on a Washington County farm with a new wife. Hannah was a couple of years older than he and had probably been widowed, leaving her to attempt to tend a farm entirely on her own—on her own, that is, except for the company of her only daughter Charlotte. In Earl, Hannah found a replacement for the husband she had lost on the farm. In Hannah and Charlotte, Earl found replacements for the family he’d lost when first Theresa died and then Danna passed away. For Earl, it was a time of returning to the farm, with new expectations borne of difficult experiences.

Did Earl live happily ever after? I wish there was a simple answer to that question. I can tell you only that there is evidence (or lack of evidence) for either that conclusion or its opposite. Listen Earl Baldwin is buried beside Danna Baker Baldwin in the same cemetery where they buried their daughter Theresa in 1911. He lived the remainder of his life in Washington County, although there is no trace of Hannah (or Charlotte) beyond their brief enumeration in the 1930 census. Did Earl and Hannah divorce? Or live joyfully together for decades to come? That, I cannot say. I know only that Earl died in 1962, having reached his 84th birthday. He lived and died attached to the farmland, community, and family connections of Washington County, New York. He may or may not have lived the life he planned; we can only hope he eventually embraced the life he lived.