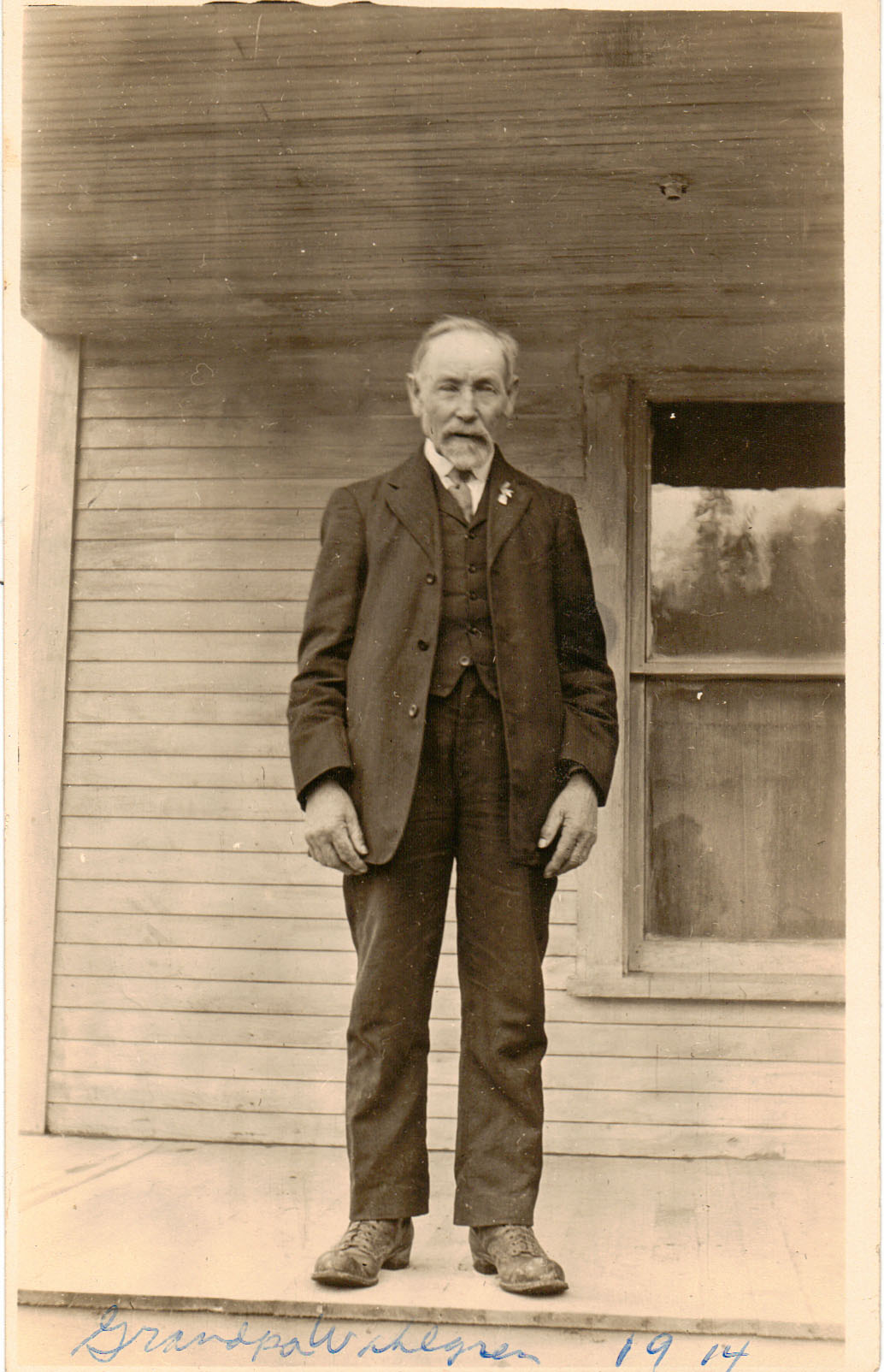

Even if it had been a novel I was holding in my hands, I couldn’t think of a more intriguing opening: Happy New Year to Anna from Charles, Jan. 2, 1907. The images that inscription inspired—the questions! Chief among them: Who was Charles? Who was Anna? Despite the photo album’s obvious age and musty odor, there was no way I could stop myself from turning the pages. They were, of course, filled with the sort of images you might expect from turn-of-the-century Washington State: families posed on porches for special occasions, high-buttoned boots and starchy collars, grey-scale ghosts from times gone by. But there was one additional feature that made the album irresistible to me. In gracefully scrolling Palmer penmanship, someone (Anna presumably) had playfully captioned several of the album’s photos. She’d written, “Snooks and Unky Fred,” beneath a photo of a small child (dressed as if to pose in a Morton Salt ad) standing beside a wooden-faced young man. “Our ‘Lodge’ in the Wilderness,” labeled a decidedly unglamorous, snow-bound cabin. Most useful of all, “Grandpa Wahlgren” appeared beneath a whiskered gentleman who had probably been at his prime during the last days of the Civil War.

Bless your heart, Anna, I thought to myself. You gave me all the clues I need.

For less than $10, I bought the album from the bored teenager manning the Antique Arcade that Saturday and brought it home.

Family photos of this vintage are precious to me—and not just photos of my own ancestors. One of the greatest joys I’ve ever experienced is being contacted by descendants of families I’ve written about on the Auburn Pioneer Cemetery website. I used to dread finding messages from these people in my inbox, scared that they would be offended that I had written about their ancestors in such a public forum. But the reality of these communications has been just the opposite. Instead, the descendants are often thrilled that their loved ones have been remembered, and they share memories and details that flavor the stories in a way that the dried crumbs of vital statistics never could. And, sometimes, they contribute scans of their own family photos to illustrate the website. I treasure these photos. For me, they bring the stories to life, often elevating them from plain-Jane obituary to textured biography.

Looking through Anna’s precious photos in that antique store, I felt the same urge to rescue that many people feel when confronted with a lost puppy marking time at an animal shelter. I had a visceral need to take that album home and care for it—to bring those faded images into the world where they could be admired, and maybe even reunited with the family who had carelessly lost track of them. If I didn’t do it, who would?

Over the next few weeks, using the handful of clues Anna had left behind, I slowly pieced together the story of her and Charles’ lives.

Anna Christina Naslund had been born in Sweden, but came to America with her family while still a young girl. Several of her younger siblings were born in Kansas where the family first settled. By the early days of the 20th Century, however, the Naslunds had relocated in Washington State. Here, in 1904, on a warm July Wednesday, both Anna and her younger sister Ida married their sweethearts in a double wedding ceremony.

Ida’s beau was named John Bravo, but I know very little about him. Anna, however, married Charles Abraham Wahlgren and moved with him to the small, logging community of Sedro Wooley, Washington. By New Year’s Day of 1907, Anna and Charles had been married for almost three years and had a baby boy named Nelson. Later that same year, Anna would give birth to their second child, a daughter named Vernet. Eventually four children would be born to the couple.

During their Sedro Wooley years, Anna corresponded regularly with her friend Freda Naylor. A large portion of her photo album is devoted to snapshots and clippings that Freda sent to Anna to keep her up-to-date on her own family’s doings. Anna seemed to have also maintained a close bond with her baby brother Fred Naslund. He appeared in several of her photos and is undoubtedly the “Unky Fred” posed alongside the indomitable “Snooks.”

Charles and Anna lived typical lives for their time. He worked as a moulder in a foundry, and she, of course, was a wife and mother.

By 1930, Charles and Anna were living apart. He had relocated to Seattle with their son Nelson who was, at that time, a department store salesman. Charles continued his work as a foundryman in Seattle. It’s impossible to say if this separation was the result of a marital rift or simply a relocation to facilitate a career opportunity. Either way, Anna rejoined Charles sometime before the 1940 Census. They remained in Seattle the rest of their lives; Charles passed away in 1955 and Anna followed in 1968. They are buried together in Seattle’s Evergreen Washelli Cemetery.

The point of all this genealogical research was to identify families who might be interested in the photo album’s contents. There were three: The Wahlgrens, the Naslunds, and the Naylors. I created basic family trees for each and uploaded them to one of the online genealogy sites. I then attached scans of every photo that I could identify to individuals within those family trees. Anyone researching those families should run across the trees and discover the attached photos. These can be copied onto their own trees and be made available to additional researchers. I’m pleased to see that this copying & spreading process has already begun. The more people who have access to these family photos, the more likely they are to survive into the future.

My fondest hope is that I someday hear from a descendant of Charles and Anna—some grandchild or great-grandchild who has developed an interest in family history—someone who will be pleased to take custody of Anna’s album with its original photos and will give them the care and preservation they deserve.

Until then, the images are out there, released into the public domain, where I hope they will continue to delight others the way they have delighted me.